RPG analysis - I screen, you screen, we all screen for GM screen

I screen, you screen, we all screen for GM screen

humble tool, status symbol, relic of a fading past

This is not a peer-reviewed academic article.

This is the end-term essay for the Media Archeology seminar, a module within the broader Bachelor in Digital Media Studies.

Written by Alessandro Piroddi.

Submitted on the 7th of November 2022.

Re-edited and published on Patreon on the 14th of Jan 2023.

Enjoy...

Intro

This paper aims at presenting a biography, albeit minimal and only partial, of an object commonly known within the community of tabletop roleplaying game players as “GM Screen”. I intend to briefly trace its history, from first appearances and original conceptualization, to contemporary takes and newer versions. In so doing I will consider the object not only as a physical product and a practical tool to facilitate play activity, but also as a socio-cultural symbol and a carrier of (game-related) ideology.

Culture vs Technique

A “tabletop roleplaying game” (ttRPG) is a ludic activity consisting in a conversation amongst the participants to the game. This conversation focuses on describing imaginary characters interacting with a shared imagined space. The most important elements of this conversation happen according to specific procedures intended to inject the activity with elements of alea, meaningful choice and persistent consequences, turning a free flowing chat into an engaging game. These procedures are usually acquired from a combination of two different sources: written texts and oral culture. The relationship and tension between these sources has shaped the design of ttRPGs in their fifty or so years of existence, which in turn has influenced the tools and aids produced to facilitate the play activity. Many objects can claim to be iconic in this regard: polyhedral dice, character sheets, a table full of unhealthy snacks, the composite of pencil and paper (and the too often forgotten gum eraser). All these tools have changed little in the past half century of ttRPG play; sure, their physical form has evolved with modern technology, but their core function and meaning is the same today as it was in the late ‘70s. This is not true for the “game screen”.

The Original Product

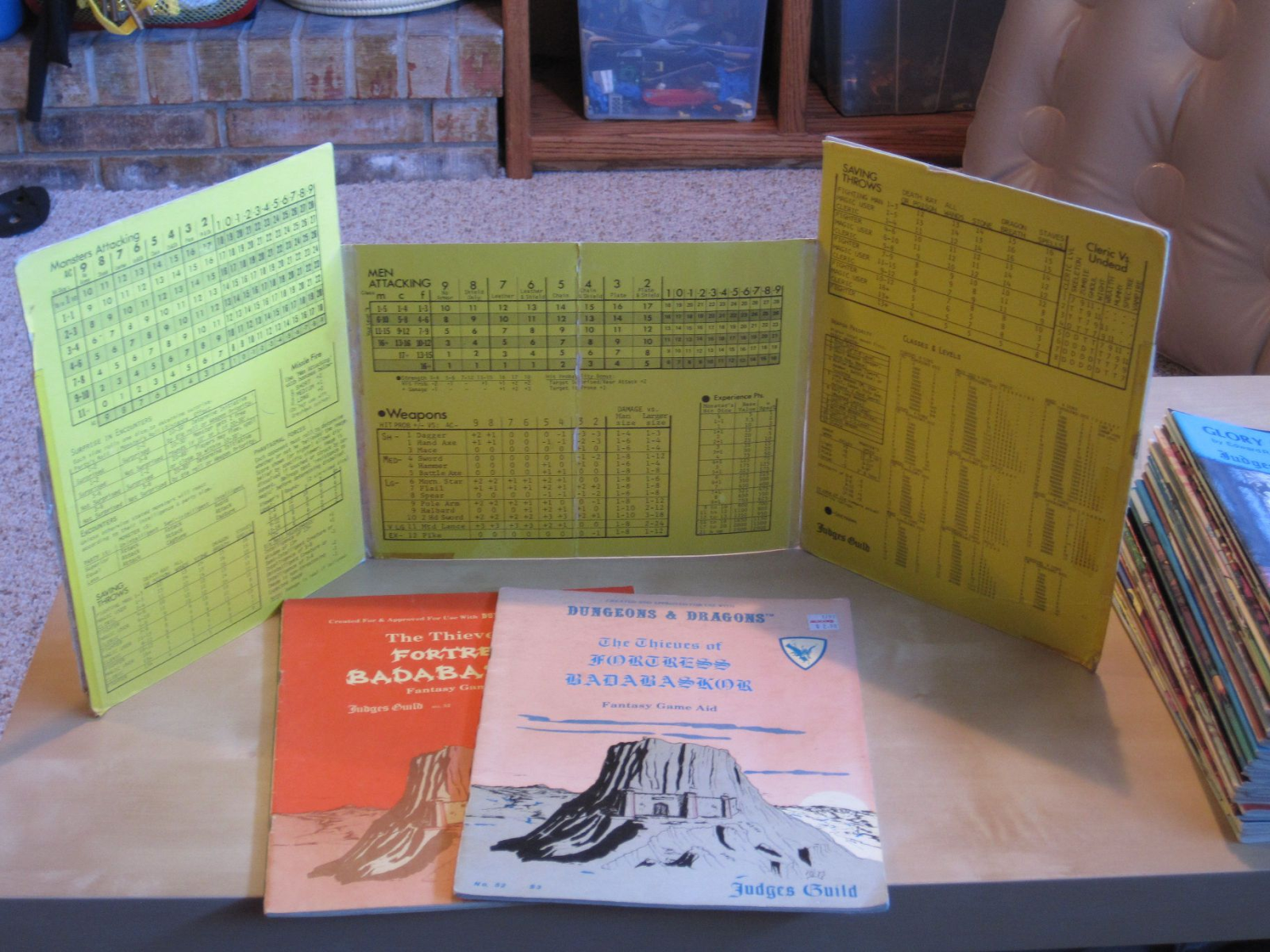

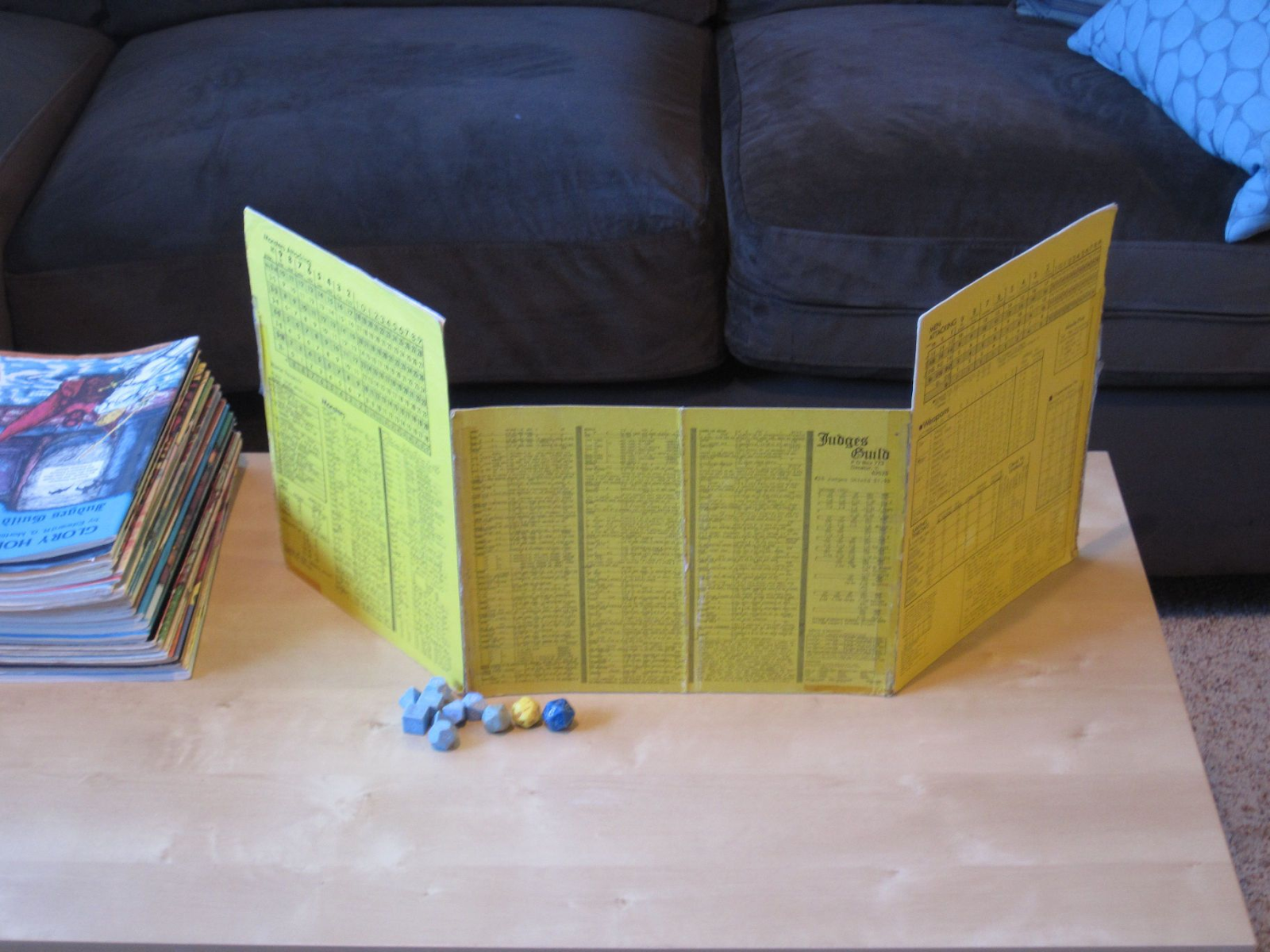

The first ttRPG game screen produced commercially was, of course, a licensed play aid for D&D called the Judge’s Shield, crafted and sold by the Judges Guild company in 1977 (Schick, 1991, p.24). This was three whole years after the original 1974 edition of Dungeons & Dragons had been published by TSR (Appelcline, 2014, p.14). The object was a simple set of three cardboard sheets meant to be taped together to form a “screen” that would serve three main purposes:

- It worked as a summary sheet for commonly used rules and mechanics, helping the game to flow more smoothly by eliminating a fair amount of page-flipping through the rulebook.

- It created a physical barrier between players and the game-relevant information held by the GM, preventing them from spoiling their own experience by accidentally looking at yet-hidden adventure notes, modules and maps.

- The same barrier made it effortless for the GM to hide their play activities in order to more directly manipulate the game experience as they deemed best.

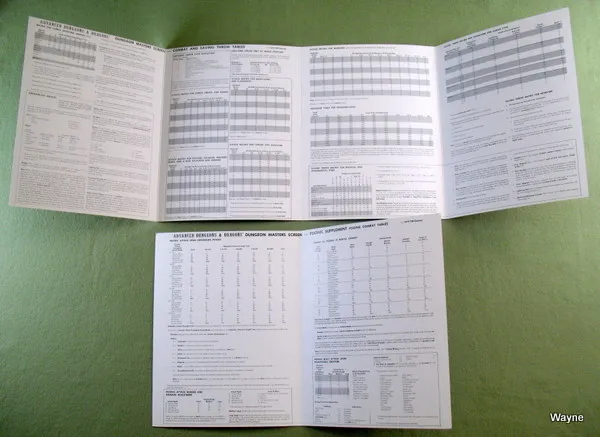

It is very important to notice how this first incarnation of the screen, and the ones immediately following it produced by the Judges Guild for other RPGs of the time, presented rules summaries on both sides: one side with GM-only rules, the other with Player-only rules.

|

|

|

| Source: RPGgeek, 2022. | |

This detail speaks of how the object per-se was mainly a utilitarian tool meant for the benefit of all parties involved. RPGs are games with asymmetric roles and tasks, and creating an obfuscating veil, a visual barrier, a screen, facilitates some of those tasks.

The physicality of the object itself, coming as a set of individual sheets that the end user needed to tape together, was most probably just a production artifact stemming from a choice made by a small publisher trying to save on costs by avoiding a specialized printing and folding process, but in hindsight we can see how it fit well in the still amateurish and do-it-yourself RPG culture of the late 70s, a trait that would go on to fundamentally characterize future RPG cultures trying to rekindle, emulate and even reimagine the “old school way” of playing RPGs.

The TSR Approach

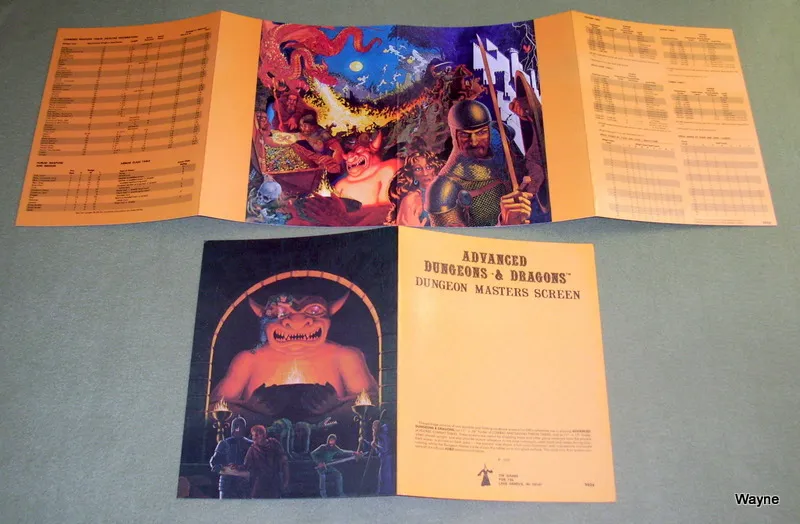

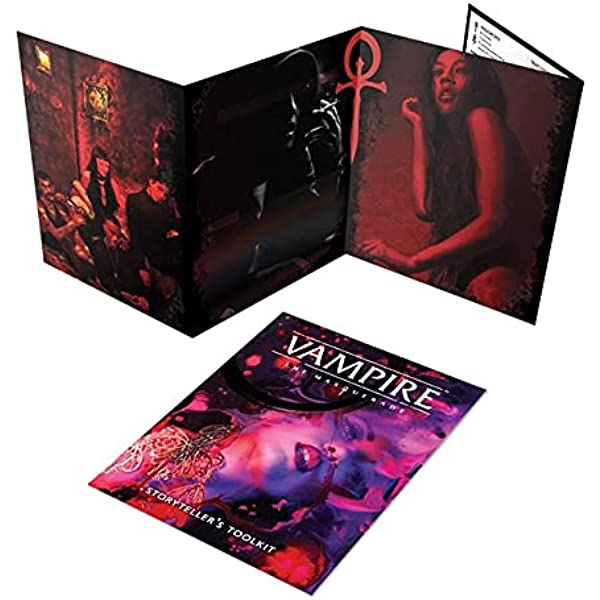

Due to the product’s immediate and spreading success (Appelcline, 2014, p.191), TSR released in 1979 its own official version of the screen (Schick, 1991, p.95), with three fundamental differences. The first was to sell the screen as a single piece of folded cardboard presented as a four-panel curtain, removing the need for DIY actions from the users and lending to the object a much more polished and “official” look. The second was to craft it for use with their brand new edition of the company’s best selling game, making it a 1977 Advanced Dungeons & Dragons aid largely incompatible with the previous 1974 edition of D&D. The third and final difference was the almost complete removal of the Player-facing rules summaries: the screen now presented GM summaries on one side and a captivating illustration on the central panels of the other side, leaving the Players with just the lateral panels presenting table for experience and weapons. This was certainly a useful reference for the game, but lacked a lot of the Player-focused info present in the original Judge’s Shield. The main screen was accompanied by an additional two-panel folded cardboard sheet, more a folio than an actual screen, with still more rules for the GM.

|

|

| Source: Wayne’s Books, 2014. | |

Again, considering the game culture implications of the design choices behind this product can be interesting.

On the one hand we have TSR and Gary Gygax pushing a corporate agenda aimed at maximizing sales by distancing OD&D from AD&D: Advanced D&D was being presented as a more professional product, a more polished and refined experience, in many ways superior and preferable to the original 1974 game. Play groups needed official rules, more precise, more complex, more complete rules, and the GM screen reflected this (Gygax, 1979, p.29).

On the other hand we can notice the first signs of how the RPG culture was slowly but steadily shifting towards a different understanding of the role of rules, Players and Game Master within the game. Players don’t need aids that remind them of the game rules, in fact AD&D includes in its Player’s Handbook only the character generation rules and a few combat elements, leaving the complete rules for the Dungeon Master Guide. This reframes the GM increasingly as less of a referee and more of a storyteller, requiring an obfuscating veil (the screen) to help them perform the “stage tricks” that the narrative experience demanded: from fudging dice rolls and cheating on resource tracking so that the game story will not be damaged by inconvenient mechanical results, to rolling dice for no real purpose other than to convince the Players that “something is going on” behind the screen. These techniques are explicitly described throughout the AD&D GM Guide, the book Players are forbidden from reading, and will quickly become part of the young RPG culture as broadly accepted common sense wisdom and GM know-how... at least, amongst GMs.

“As this book is the exclusive precinct of the DM, you must view any non-DM player possessing it as something less than worthy of honorable death. Peeping players there will undoubtedly be, but they are simply lessening their own enjoyment of the game by taking away some of the sense of wonder that otherwise arises from a game which has rules hidden from participants.”

(Gygax, 1979, AD&D:DMG, p.8)

This trend continued in the 1989 second edition of AD&D, but only really culminated with the 2000s iteration of the game, now simply called D&D 3rd Edition. Here the associated Dungeon Master screen was 100% evocative illustrations on the Players’ side. It is interesting to note how the theory of play and the practice of it started somehow diverging more markedly. Now the Players Handbook featured complete combat rules, and the Dungeon Masters Guide had lost most of the text that too blatantly instructed the GM to cheat for the good of the play experience (although there still was plenty of less blunt but quite clear text going in that direction). But at the same time the practical tools of the game, exemplified by the GM screen, told a different story, one begun more than 20 years prior and that had deeply influenced the root values of RPG culture.

|

|

|

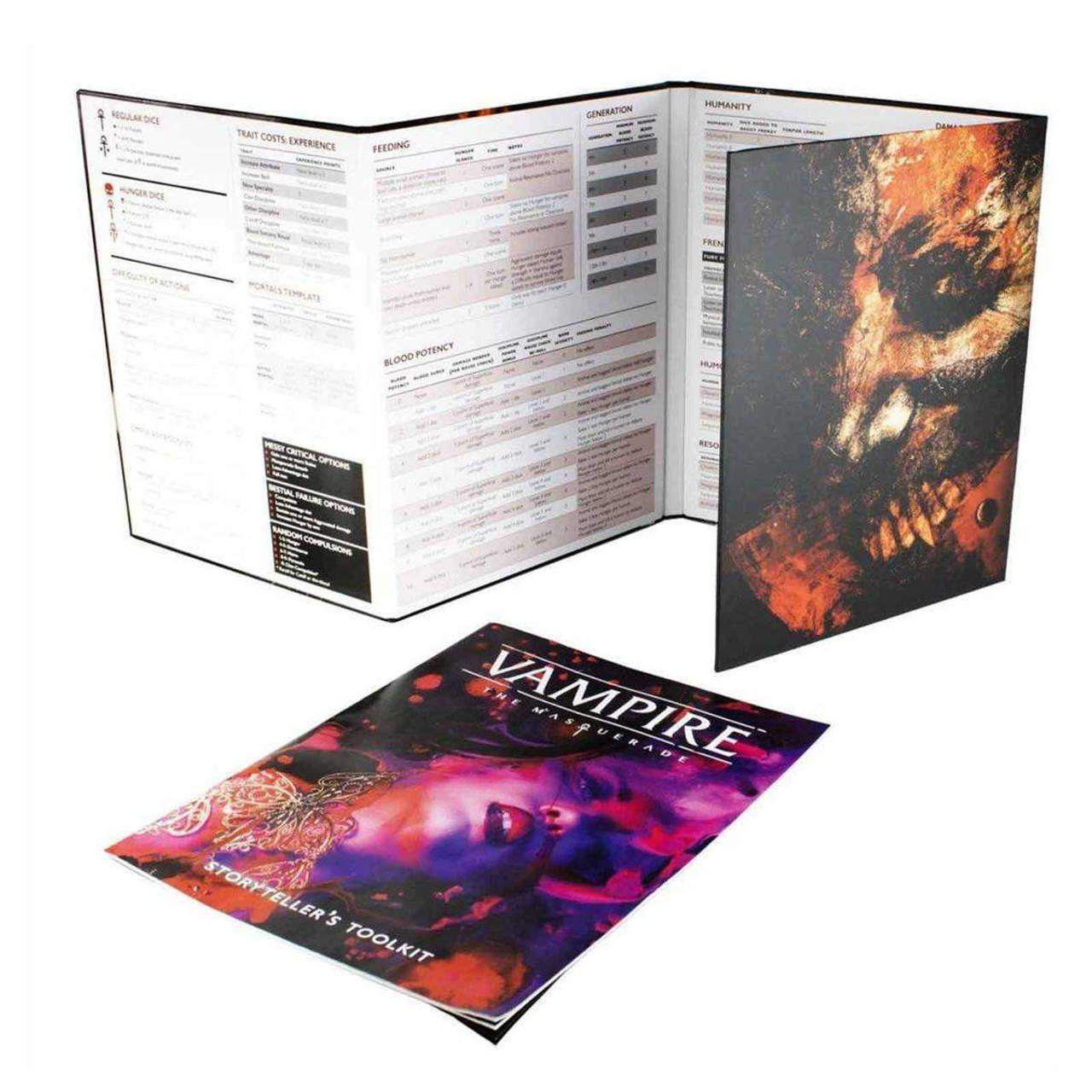

| Vampire the Masquerade 5th Edition - Storyteller Screen

Source: Renegade Game Studios |

|

The screen had shifted from being a simple tool aiding all the game participants in handling the complex rules of their play activity, to an element of separation between Players taking on the roles of fictional characters and a different Player taking on a role more and more akin to that of a stage director, the writer and narrator of an interactive story on whose shoulders rested the vast majority of duties, tasks, powers and expectations pertaining to the play activity. It should be mentioned that this was not a D&D-only phenomenon, as pretty much every RPG with the financial resources to produce a GM screen did so. And they did it following TSR’s lead: GM info on one side, pretty pictures on the other.

Illusionism

This trend towards a style of play where the GM abandoned the role of impartial referee of a quasi-sports-like activity to instead dress the garbs of a storyteller is best surmised by the term “illusionism”:

“Illusionism

A family of Techniques in which a GM, usually in the interests of story creation, exerts Force over player-character decisions, in which he or she has authority over resolution-outcomes, and in which he tries to maintain a Black Curtain to conceal his control over events.”

“Black Curtain

The effects of a variety of Techniques a GM may employ to keep his use of Force hidden from the other participants in the game, such that they are at least somewhat under the impression that their characters' significant decisions are under their control.”

“Force

The Technique of control over characters' thematically-significant decisions by anyone who is not the character's player.”

(Edwards, 2004 / 2011)

The term “illusionism” was coined by Paul Elliot in 2002, during the first years of the RPG design movement born around the Forge forum, run by Ron Edwards. While born with other purposes in mind, as RPG culture shifted overwhelmingly towards illusionism the GM Screen as an object became literally the physical manifestation of the black curtain effect, increasingly representing the role of GM in a unique and iconic way, just like the twenty-sided polyhedral die is symbolic of RPGs generally and D&D specifically.

Status Symbol

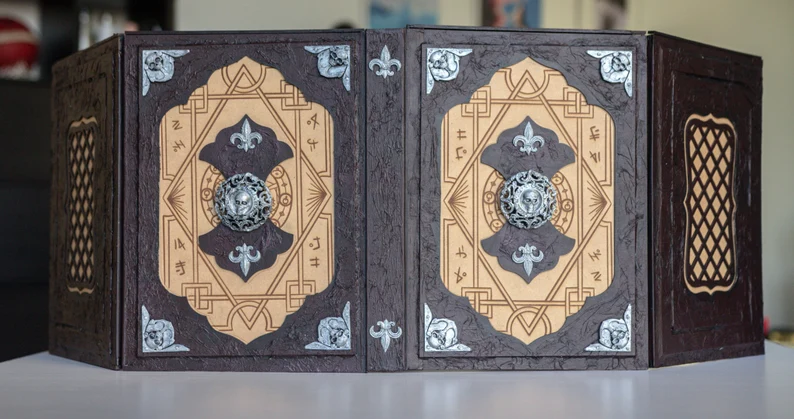

As official GM Screens kept being produced for each new edition of every major mainstream game, their ubiquity and iconic status increased, leading passionate RPG hobbyists to devise their own artisanal screens, usually for personal use but more and more often also for commercial purposes, as the demand for such objects increased and internet facilitated independent communication and commerce. Eventually, a number of third-party companies picked up on the trend and nowadays there are plenty of “high level” GM Screens that can be acquired for an appropriately high level price.

These objects differ from the ones sold by first-party RPG in that they abandon the simplicity of the official products (folded cardboard panels printed with text and illustrations) to craft unique, luxurious and even baroque objects of desire and status: engraved or branded wood paneling, leather or cloth bindings, metal hinges and decorations, complex structures that allow the screen to take on the shape of a book, a treasure chest, a set of gates, or even a full fledged castle complete with wall sections, towers and portcullis.

|

|

|

| Sources: etsy.com and fatdragongames.com | |

The pinnacle of this product family must be the modular GM Screen crafted by Wyrmwood Gaming that, at the apex of its options, offers: four panels of precious wood (ebony exterior and cherry interior) decorated on the outer side by a shield-shaped central insert made of gemstones (such as amethyst or obsidian) while the inside sports a topside magnetic strip (to pin sheets and notes) and six magnetic buttons (to attach special panels and accessories); in between panels one can fit “towers” with various functions (still in ebony) such as a two-sided dice-rolling tower and a six-stories storage tower; behind the screen the GM can place an hexagonal dice tray and a tablet tray (again, in ebony); on top of each panel’s edge a groove allows the placement of black and white chalkboard tokens to keep track of hero and monster names, which can be crowned by a brass counter to track turn order and initiative; finally, each panel interior can fit (thanks to the 6 mag points) an acrylic slate, allowing the GM to wet- write/erase on top of maps, or a full sheet of metal, to allow for the affliction of more magnetic components. According to the Wyrmwood pre-order website this would amount to over 20 components at the total price of 2,765$, plus shipping. The Kickstarter/Backerkit campaign that funded this project gathered almost 5 million dollars across more than 8 thousand backers (Wyrmwood, 2022).

|

|

| Source: Wyrmwood Youtube channel |

We can see how GM Screens have shifted from having rules on both sides, to only on one side, to none at all. This is partly because they aspire to be used with a variety of different RPGs, offering instead spaces and tools to clip sheets of notes and rules to the inner panels, but probably also because the contemporary illusionism-focused RPG culture has established as common wisdom the idea that game mechanics are merely a soft guideline at the GM’s disposal, to be ditched whenever the GM deems it to be in the way of their personal definition of “fun”. Observing the physical characteristics of these artisanal/luxury screens it appears obvious that they are meant more as an aid to handle GM notes and prep-work, rather than keep rules summary sheets at hand. And, beside the most obvious practical function, these screens more than ever represent a symbol of power and status, of division between the literal “master” of the game (tasked by the illusionist playstile to de facto be the game rather than just one participant amongst equals) and their “interactive audience” of Players.

Minorities

While illusionism reigns supreme within the culture of mainstream commercial RPGs, there are a few vocal minorities that have a very different relationship with the GM Screen object.

On the one hand we can find a galaxy of RPG groups either sticking to, or rediscovering anew, the “old school” way of playing, either using the original older editions of various RPGs, their modern and updated retroclones, some newer but nostalgic game, or even the current editions of mainstream RPGs but running them according to heavy cultural influences from the old way. This subculture, that in all its many sub-varieties can still be generally called Old School Renaissance, cares little for GM Screens beyond their most basic functionality of hiding the adventure’s map and notes, as their GM, their Referee, often makes a point of rolling dice in front of the screen, in the open when Players can see, exactly to demonstrate their honesty, integrity and lack of illusionism.

On the other hand we can look at the culture of “indie” or “modern” game design that started flourishing around the early 2000s thanks to the seminal influence of the Forge forum. The games spawned by this culture, and its various internal currents, have a more boardgame-like approach to the RPG experience in so far as they consider the game rules as the cornerstone of play, allowing game participants to enact a unique narrative and play experience. While exceptions exist, by far and large the design of this games and the resulting play culture it produces have little use for GM Screens:

- many of these designs have relatively simple rules (at least in comparison to most mainstream RPGs)

- these rules focus more on procedure and table behavior than on calculations and minutiae

- the GM is often required to fully or partially improvise many key aspects of the game experience, thanks to the support of the aforementioned rules and procedures

- the GM is construed as simply another Player among equals, which happens to follow a different set of procedures, but is nevertheless bound by them (ignoring rolls and rules is seen as cheating, not as a GM prerogative)

- many such RPGs actually eschew the role of GM entirely, distributing its tasks, duties and powers amongst Players

For all these reasons such modern designs tend to rely more, if at all, on simple summary sheets that lay flat on the table, rather than fashioning them as vertical barriers.

The Future

As in most things, technology is affecting the nature of GM Screens too. Online play, both the rudimentary “video call” and the cutting edge “virtual tabletop”, completely removes the need for a physical GM Screen, as in both cases the only thing people can see are each other's faces or whatever the platform host (usually the GM) chooses to show on screen.

But even when playing in person, the fact that many GMs have started using portable electronic devices to handle game elements and personal notes is rendering GM Screens obsolete: the screen of a laptop or tablet constitutes a “natural” barrier between Players and GM, perfectly hiding game content from sight and even granting that sense of separation that some RPG cultures value. The only limit is the obfuscation of GM-side dice rolls, which can be achieved through many other means: rolling dice in a cup or tray is often sufficient to hide the results from people sitting anywhere but right next to the GM; alternatively, dice-roller software is plentiful and very easily accessible from phones, tablets and laptops.

The current accessibility and ubiquity of personal electronics is rapidly eroding even the last vestiges of practical value that a GM Screen has, leaving in their place an object that serves a purely decorative and symbolic function as it has become not uncommon to see RPG tables where a GM Screen sits in front of an electronic device: it’s traditional and expected, it signals the GM’s place and importance, it is part of a “ritual” that turns a normal meeting space into a game-dedicate one.

Reference List

Appelcline, Shannon (2014). Designers & Dragons: The ’70s. Evil Hat Productions.

Edwards, Ron (2004). The Forge Provisional Glossary. Published 08.05.2004. Last accessed 26.10.2022.

http://www.indie-rpgs.com/_articles/glossary.html

Edwards, Ron (2011). The Big Model Wiki - Illusionism. Published 14.02.2011. Last accessed 26.10.2022.

https://big-model.info/wiki/Illusionism

Gygax, Gary (1979). “D&D, AD&D and gaming”. Dragon. 3: 12: 28-30.

Gygax, Gary (1979). Advanced Dungeons & Dragons : Dungeon Masters Guide. TSR Games.

Renegade Game Studios - VtM5 ST Screen. Last accessed 03.11.2022.

RPGgeek - Judge’s Shield 1977. Last accessed 19.10.2022

https://rpggeek.com/rpgitem/49524/judges-shield

Schick, Lawrence (1991). Heroic Worlds: a history and guide to role-playing games. Prometheus Books, Buffalo, New York.

Wayne’s Books. “RARE 1ST PRINT: AD&D DM Screen set”. Game Gallery - Photo Blog. Published 27.03.2014. Last accessed 20.10.2022.

https://waynesbooks.games/2014/03/27/add-dm-screen-set-rare-1st-printing

Wyrmwood Games. Backerkit Preorder page. Published July 2022. Last accessed 27.10.2022.

https://gm-screen-by-wyrmwood.backerkit.com/hosted_preorders

Files

Get UnPlayableGames D-Blog

UnPlayableGames D-Blog

A den of iniquity and posts about funky design ideas.

| Status | Prototype |

| Category | Other |

| Author | Alessandro Piroddi |

| Tags | blog, Game Design, rpg-culture |

More posts

- RPG analysis - Why Grognardpunk? _itchAug 24, 2023

- RPG analysis - Do roleplayers dream of algorithmic sheepSep 06, 2022

- RPG analysis - Narratives Against the Time-MachineMay 24, 2022

- RPG analysis - Myths of PlayMay 06, 2022

- Talking about the Grognardpunk ManifestoApr 22, 2022

- RPG analysis - The rulebook made me do itMar 28, 2022

- Modern RPG design - the Good the Bad and the MoneyFeb 08, 2022

- RPG Design Theory Primer #01 - CoherenceFeb 01, 2022

Leave a comment

Log in with itch.io to leave a comment.